ITD Summer Institute

Western Component

Field Trips

Liberty Park

The largest and most central property of the city's public park system, this 80-acre playground offers recreational activities for all: the Children's Garden and boating pond, playground, amusement park and snack bar, swimming pool and a tennis park with 16 lighted courts. Recent developments have added a system of interactive pools and fountains to depict the topography of the Salt Lake Valley.

Chase Museum of Utah Folks Arts

Picnic Dinner

- Chicken Pasta Salad

- Potato Salad (with eggs)

- Corn Relish

- Melons

- Challah Rolls

- Lemonade

Jordanelle Reservoir

Dams in Utah: http://www.usbr.gov/dataweb/html/utdams.html

Jordanelle was last major dam to be built in Utah. As part of the Bonneville Unit of the Central Utah Project it was proposed as an alternative to other storage dams on the Provo River, and was selected as the most economically feasible. When filled, waters impounded from the Jordanelle Dam inundated the two small hamlets of Hailstone and Keetley.

The Jordanelle Dam site was challenged by various interests. One concern was that the site was geologically flawed. This argument was strengthened following the Teton Dam failure in 1976. There was concern from Park City mining interests that construction of the Jordanelle would flood sections of the Ontario Mine, prohibiting future mining there. Within Salt Lake County there was opposition to the Jordanelle and the whole Central Utah Project. A Salt Lake County Attorney's report suggested that backers of the CUP artificially created the need for the very expensive reclamation project. The report added that more efficient use of available water and increased development of ground water would solve the water crisis in Salt Lake and Utah counties. Other concerned citizens questioned the constitutionality of the CUP as well as the high cost of the Bonneville Unit.

Uintah Ouray Reservation

The intrusion of Mormon settlers onto Utah Indian lands in 1847 touched off an extended period of conflict between Mormons and several Ute (Nuciu) bands in particular. By 1860, Ute Indian agents suggested removing these Indians to the Uintah Basin. Brigham Young agreed to the proposal after satisfying himself that the isolated area was "one vast contiguity of waste," fit only for "nomadic purposes, hunting grounds for Indians and to hold the world together." In 1861, Abraham Lincoln set aside the Uintah Valley Reservation, comprising 2,039,400 acres in the Uintah Basin. By 1870 most members of the Tumpanuwac, San Pitch, Pahvant, Sheberetch, Cumumba, and Uinta-at bands of Utah Utes (collectively called the Uintah Band) resided on the Uintah Reservation.

In 1881, following a uprising of Colorado Utes, the federal government forcibly removed members of the Yamparka and Parianuc bands (known as the White River Utes) to the Uintah Reservation. The peaceful Taviwac (Uncompahgre Utes), led by Chief Ouray, could not escape removal, but managed to obtain their own reservation in 1882 -- the 1,912,320 acre Ouray Reservation, situated on the Tavaputs Plateau, immediately south of the Uintah Reservation. The two reservations maintained separate agencies at Whiterocks and Ouray until the Bureau of Indian Affairs merged their administration in 1886. The Indian agency was moved from Whiterocks toFort Duchesne after the military post closed in 1912.In 1888 Congress removed a triangular "strip" of 7,004 acres containing valuable Gilsonite deposits from the eastern end of the Uintah Reservation, and in 1897 mining interests influenced Congress to begin allotment of the Ouray Reservation. In 1904, Congress approved 80-acre individual allotments for the Uintah and White River Utes of the Uintah Reservation. The Uintah-Ouray Reservation shrank from nearly four million acres in 1882 to a jointly owned 250,000-acre grazing reserve and 1,283 individual allotments totaling 103,265 acres by 1909. In 1905 the federal government withdrew over 1,100,000 acres for the Uinta National Forest and 56,000 acres in 1909 for the Strawberry Valley Reclamation project, throwing the remaining reservation land open for public sale. Sales of individual allotments further reduced Northern Ute holdings.

Following the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, the Northern Ute Tribe began repurchasing alienated reservation lands. In 1948 the federal government returned some 726,000 acres to the tribe in what is called the Hill Creek Extension. In a 1986 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld an Appeals Court ruling granting the Northern Ute Tribe "legal jurisdiction" over three million acres of alienated reservation lands -- an important decision for the future of the tribe and the region.(See: http://www.onlineutah.com/uintah-ourayreservationhistory.shtml. Also: Donald Callaway, Joel Janetski, and Omer C. Stewart, "Ute," in Great Basin, edited by Warren L. D'Azevedo, vol. 11 of Handbook of North American Indians (1986); Fred A. Conetah, A History of the Northern Ute People (1982); Joseph G. Jorgensen, The Sun Dance Religion: Power for the Powerless (1972); Kathryn L. MacKay, "The Strawberry Valley Reclamation Project and the Opening of the Uintah Indian Reservation," Utah Historical Quarterly, 50 (Winter 1982); Floyd A. O'Neil, "Reluctant Suzerainty: The Uintah and Ouray Reservation," Utah Historical Quarterly, 39 (Spring 1971); Floyd A. O'Neil and Kathryn L. MacKay, A History of the Uintah-Ouray Ute Lands, American West Occasional Papers no. 10 (1979).)

We will be eating Indian tacos at the Ute Education Center. And a picnic lunch later in Heber or Park City:

- Southwestern Rice and Black Bean Salad

- Pasta Salad

- Spinach Dip with Baguettes

- Raw Vegetables

Park City

Precious metals in the mountains around Salt Lake City were first mined commercially in the early 1860s. Colonel Patrick E. Connor of Fort Douglas iencouraged his men to prospect with the purpose of bringing non-Mormons into the Utah Territory. The first recorded claim of the Park City Mining District was the Young American lode in December 1869. Clearly by the 1870s, production in that area had begun, perpetuated by the discovery of a large vein of silver ore in what would become the Ontario Mine. In its heyday, it was considered the greatest silver mine in the world.

In May 1872, George Snyder and his family arrived in the mountain valley. Awed by the lush grasses and blazing wildflowers he christened the area, "...Park City, for it is a veritable park." In 1884, Park City incorporated. Prospectors found that silver proved to be abundant and dozens of mines in the Park City Mining District actively made shipments by the 1880s. The Daly Mining Company and Anchor Mining Company were two of the first major producers doing so well that even the national financial panic of 1893 had a marginal impact.

The mining boom of Park City brought hundreds of prospectors into the area. They set up camps along the hillsides near the mines, bringing with them diverse religions and ethnic traditions. Between 1870 and 1900, Park City's population increased by 40 percent. Originally, the town consisted of boarding houses, mills, stores, saloons, prostitute "cribs," theaters, and mine buildings. But by the 1880s, many prospectors had either sent for their families or were bringing them along, building houses and establishing schools. The first school in Park City was St. Mary's School operated by the Sisters of the Parish of St. Mary of the Assumption. City officials also organized sanitary committees and established a water system, telephone service, and chartered a fire company.

A number of spectacular fires mark Park City's history. Built primarily of wooden structures, the town experienced its worst destruction in June 1898. Canyon winds fanned the flames of an early morning fire. Within seven hours three-quarters of the town had burned causing over one million dollars in damage. The blaze was the greatest in Utah history. It left Main Street in ruins with only a few gaunt walls remaining of the 200 businesses, houses, and dwellings. Front-page newspaper headings put the fire alongside stories of the Spanish-American War. In the residents' haste to rebuild their town, they again built wooden structures in very close proximity, leaving the town vulnerable to future fires.

By the turn of the century, Park City mines had made such men as David Keith, Thomas Kearns, John Daly, John Judge, and Ezra Thompson, very wealthy. Class differences in Park City were instant and complex. Miners came from such places as the depleted mines in Nevada, Scotland, Ireland, and Scandinavia. Many of the Chinese who had worked on the transcontinental railroad came only to suffer severe bigotry. Societal status depended on one's economic holdings, occupation, ethnicity, religious affiliation, and membership in fraternal organizations. In Park City, success was enjoyed by a few, but produced by many; fortunes were made and lost, ultimately making millionaires of twenty-three men and women.

The mining industry had a large impact on the economy of Utah, accounting for 78 percent of the state's total exports in 1882. Mines stayed healthy initially by merging or buying out weaker competitors. In 1925 the Park Consolidated Mining Company formed by merging Park City Mining and Smelting Company with the Park Utah and the Ontario Silver Mining Company. The new company discovered a gigantic body of ore and by 1928 emerged as the largest single silver producer in the United States.

Shortly after World War I the mines experienced serious labor unrest. The only strike in Utah led by International Workers of the World (IWW) was in 1919, but lasted only one month. Other strikes persisted and the economy faced further crippling by the Great Depression. Oddly, the great demand for metals during World War II actually caused Park City mines to experience further suffering. By the 1950s, fewer than 200 men worked in the mines and Park City became distinguished as a "ghost town."

The late 20th century Park City transformed into a recreational facility. The Park City Ski Area was opened and the old mines were open to tourists. In a 1990 poll, it ranked second among North American ski resorts, leaving a legacy that had produced by the early 1960s, a total value of $500 million in silver, gold, lead, and zinc.

(See: http://historytogo.utah.gov/places/olympic_locations/historyofparkcity.html; David Hampshire, Martha Sonntag Bradley and Allen Roberts, The History of Summit County )

Kennecott Copper Pit

Important in the formation of the Utah copper industry in the late

nineteenth century were Enos A. Wall, Samuel Newhouse, Daniel C. Jackling, and

the Guggenheim family. Wall appreciated the potential of low-grade porphyry

copper deposits and acquired important claims in Bingham Canyon in 1887. By 1890

underground copper mining had begun in the area. Daniel C. Jackling, a

metallurgical engineer, and Robert C. Gemmell, a mining engineer, examined

Wall's properties for Captain Joseph R. DeLamar's mining interests. They

proposed mining these low-grade ores from the surface, a practice today called

open-pit mining. They believed that the mass mining and production of low-grade

copper ores was not only possible but also could be profitable. In 1898 Samuel

Newhouse and Thomas Weir formed the Boston Consolidated Mining Company.

In 1903 Jackling and Wall established the Utah Copper Company. The company

immediately constructed a 300-tons-per-day (TPD) gravity pilot mill at Copperton.

By 1905 Jackling had persuaded Guggenheim Exploration to underwrite a

$3,000,000 bond and purchase $500,000 of Utah Copper stock. This helped to set

the stage for the first open-pit mining in Bingham. In 1906 steam-shovel

operations began, with steam locomotive trains removing material from the

canyon. Also that year, Kennecott Mines Company, named (although with altered

spelling) for explorer and naturalist Robert Kennicott, was organized in Alaska

by Stephen Birch, and the American Smelting and Refining Company (ASARCO)

started the Garfield Smelter to process Bingham ores.

Beginning at the turn of the century, a large influx of immigrants from southern

and eastern Europe and from Japan arrived in Utah to provide needed labor for

the mining industry. In 1912 the Western Federation of Miners sought union

recognition and, supported by a large contingent of immigrant laborers, struck

Utah Copper Company. The strike did not win union recognition but did oust

Leonidas Skliris, the dominant Greek labor agent, from power.

As the worldwide Great Depression hit in 1929, Utah Copper constructed a

precipitate plant at the mouth of Bingham Canyon. In 1936 Kennecott acquired all

the property and assets of the Utah Copper Company. That same year

molybdenum (a metal used to strengthen steel) separation facilities were

established at the Magna and Arthur mills. Construction of the central yard for

expansion of rail operations began in 1937. Union recognition came in 1938 as

Kennecott viewed unions as official employee bargaining representatives.

Wartime copper production pushed Kennecott into the national spotlight. In fact,

the Bingham Canyon mine established new world records for copper mining and

produced about 30 percent of the copper used by the Allies during World War II.

During the war years many women worked in the mine, mills, and smelter. In 1944

the construction of its own power plant rendered Kennecott independent of

outside sources for electrical power. That year also produced the first

collective bargaining agreement of wages and working conditions.

Kennecott expanded its power plant in 1960 to a 175,000-kilowatt capacity. By

1961 Kennecott's copper mines included four large open pits in the western

United States and one underground mine in Chile. In addition to those in Utah,

operations existed in New Mexico, Arizona, and Nevada. In 1963 the company began

a four-year, $100,000,000 expansion of operations. Parts of this program led to

the 1965 opening of a cone precipitate plant at Bingham, and the Bonneville

concentrator and a molybdenum oxide production plant at the Garfield smelter in

1966.

Further expansion led to the demise of the town of Bingham, which ceased to

exist in 1971. Later in that decade, the town of Lark also succumbed to mine

expansion. In 1977 construction began at the Garfield smelter to comply with the

Clean Air Act. By 1978 the 1,215-foot smokestack at the smelter was completed.

The smelter ultimately captured 94 percent of the sulfur contained in the copper

concentrates.

The year 1980 marked the beginning of a worldwide copper recession which

initiated significant changes for Kennecott. Standard Oil of Ohio (SOHIO) in

1981 acquired Kennecott, including the company's Utah Copper operations which

had over 7,500 employees. In 1985 operations ceased at the Bingham Canyon mine.

New labor agreements were negotiated in 1986, and resumption of all Kennecott

Utah Copper operations occurred in 1987. British Petroleum acquired total

control of SOHIO in 1987, with Kennecott becoming part of BP Minerals America.

In 1988 Kennecott announced a $400,000,000 modernization program under president

Frank Joklik.

A revitalized Kennecott Utah Copper began 1988 with the completion of a

peripheral tailing discharge system at the tailings pond near Magna, and the

start-up of modernized facilities at Bingham and Copperton.

(See: http://www.media.utah.edu/UHE/k/KENNECOTT.html;: T.A. Rickard, The Utah Copper Enterprise (1919); Kennecott Copper Corporation, All About Kennecott: The Story of Kennecott Copper Corporation (1961); Leonard J. Arrington and Gary B. Hansen, The Richest Hole on Earth: A History of the Bingham Copper Mine (1963).)

Antelope Island

Fremont Indians lived on the island between 700-1300 A.D. when that Indian group ranged throughout Utah and adjacent areas of Idaho, Colorado and Nevada.

John C. Fremont and Kit Carson made the first known visit by people of European descent to Antelope Island in 1845. They killed several antelope on the island thus giving Antelope Island its name. By the 1930's the island's namesake had disappeared from Antelope Island. In 1993 a cooperative effort between the Utah divisions of Wildlife Resources and the State Parks and Recreation resulted in the reintroduction of 24 pronghorn antelope. By the 1995 fawning season the population had nearly doubled in size.

Fielding Garr established permanent residency on the island in 1848. He not only tended his own herds, but those of other stockmen as well. In 1849 Brigham Young asked Garr to manage the LDS Church's Tithing Herd, which was kept on the island until 1871. The Tithing Herd was utilized by the Perpetual Emigration Fund which was established to help needy Mormon converts immigrate to Utah. Recipients would reimburse the fund when circumstances would allow them to do so. Reimbursement was made in the form of livestock, which was considered better than cash. During this time the LDS Church also invested thousands of dollars in valuable stallions and brood mares which were turned loose on the island.

Antelope Island was used as a base camp for a government funded survey of the Great Salt Lake by Captain Howard Stansbury during the years of 1849-50. During the 1870's several private homesteads were established, with George and Alice Frary staying the longest. Alice requested to be buried on her island home, and a marker stands to commemorate her grave site.

Satellite image of Great Salt Lake

Satellite image of Great Salt Lake

22,200 B.C.: Lake Bonneville, Stansbury level, 245 feet deep.

16,000 B.C.: Lake Bonneville, Bonneville level, 1,020 feet deep, as the climate

becomes wetter.

14,800 B.C.: Lake Bonneville breaks through at Red Rock Pass, Idaho, making an

outlet into the Snake Drive Drainage. Its level rapidly decreases.

14,200 B.C.: Lake Bonneville, Provo level, 640 feet deep.

10,800 B.C.: Lake Bonneville, Gilbert level, 75 feet deep, as a drier climage

exists.

10,000 B.C.: The first humans may have arrived at the lake.

8,000-10,000 B.C.: The modern Great Salt Lake emerges.

A.D. 1776: Spanish explorers Escalante and Dominguez hear tales of a bitter sea

that connects with Utah Lake.

1824: Jim Bridger and Etienne Provost become the first recorded white men to see

the lake.

1843: John C. Fremont and Kit Carson explore the lake and visit Fremont and

Antelope islands.

1847: First pioneers bathe in the lake.

1870: Lakeside and Lake Shore, the first two bathing resorts on the Great Salt

Lake, emerge.

1873: The lake level reaches a historic high of almost 4,212 feet above sea

level.

1890: Dropping lake levels decrease crowds to the lakeshore resorts.

1896: State gets ownership of the lake.

1903: Lucin railroad causeway cutoff is built near Promontory.

1963: The lake level drops to 4,191 feet above sea level.

1964: Most of the causeway to Antelope Island is built.

1969: The Antelope Island causeway opens.

1983: Rising lake levels close the Antelope Island causeway. (It was also

temporarily washed out during numerous storms from 1969-1983.)

1986-87: Lake level almost reaches 4,212 feet.

1987-89: Pumps operate to lower the level of the lake.

1993: The causeway to Antelope Island reopens after reconstruction.

1997: The lake begins to rise again.

1999: The lake's level rises 1.5 feet since 1998.

"Miners" began extracting common salt from the lake in the mid-1800s. Other

minerals like magnesium metal, chlorine gas, sodium and potassium sulfate and

magnesium chloride have been extracted since the early 1960s, said J. Wallace

Gwynn of the Utah Geological Survey. Today, six mineral extraction companies

operate near the lake, using solar evaporation to concentrate the lake waters to

glean minerals.

It is thought the Great Salt Lake contains 4.9 billion tons of salt — including deposits in the lake bed and the salty solution in the water. Much salt also remains in the West Pond that was used as a reservoir during the pump years in the 1980s.

Sodium chloride, or common salt, is harvested from commercial evaporation ponds, then collected and processed for use in water softeners or formed into salt-lick blocks for cattle.

And you can thank the lake for ice-free streets on snowy, winter mornings. Most of the salt is used locally on Utah roadways.

Table salt is not produced at the lake. It simply costs too much in processing to guarantee purity.

Salt byproducts like potassium sulfate and magnesium-chloride brine are used for commercial fertilizers and as dust suppressants.

In 1997, in excess of 31 billion

gallons of water was pumped from the Great Salt Lake by mineral harvesting

companies. Total mineral extractions from the Great Salt Lake in 1997 were

valued at about $230 million.

(See:

http://www.davisareacvb.com/attractions/antelopeislandfacts.htm)

Picnic Lunch

3 salads

cookies

Fort Buenaventura

One of the most fascinating periods inn the history of the American West is the mountain man era. Men like Jim Bridger, Peter Skein Ogden, Jedediah Smith, Etinne Provost, and Hugh Glass traded with the Indian tribes, married the Indian women, trapped the rivers for beaver, and lived off the land. The legendary rendevous, where mountain men gathered annually to trade furs for supplies and to eat, drink, and tell stories and demonstrate their skills, have become as famous as the men themselves.

In 1844-45, one of these traders, Miles Goodyear, settled e on the east bank of the Weber River.. Goodyear chose to build his fort on the Weber River because of the spot's advantages: water was plentiful, even in dry seasons; soil was rich; winters were not too severe; trout, grouse, waterfowl, deer, elk and mountain sheep available for food. It also was well located for trading because it was at the junction of two Indian trails.

Miles Goodyear's cabin was built of cottonwood logs and was surrounded by a stockade that enclosed the cabin, several other buildings and the corral. Goodyear called the place Fort Buenaventura for the mythical river believed to rise somewhere in the desert and drain into San Francisco Bay.

Fort Buenaventura has been constructed on the original site of the fort that was built in 1845 by Miles Goodyear and his Ute wife. It has been reconstructed according to archaeological and historical research. The recreated fort’s dimensions, height of pickets, method of construction, and number and styles of log cabins are all based on documented facts. There are no nails in the stockade; instead historic wooden pegs and mortis and tenion joints hold the wall together.

(See: http://www.ogden.navy.mil/history.html and http://www1.co.weber.ut.us/parks/fortb/

Ogden

The Mormons arrived in Utah in 1847. Goodyear saw the arrival of the Mormons as a means to increase the value of his property and encouraged them to settle at his site on the Weber River. Wanting to bring all settlements and land within the area under their control, the Mormons bought Goodyear's fort in 1847 for the sum of $1,950.

In March, 1848, the Mormons officially moved into Fort Buenaventura led by Captain James Brown. The name of the fort was changed to Brown's Fort and the settlement was known as Brownsville. It was not until 1850 that Brownsville was renamed Ogden after the trapper.

The City of Ogden was incorporated on February 6, 1851. A City Council consisting of a mayor, four alderman, and nine councilors administered the new city. They had the authority to levy and collect taxes on all taxable property within the city limits, and to appoint the recorder, treasurer, assessor, collectors, marshal, streets supervisor and other officers which were deemed necessary. The first Ogden City officers appeared to be appointed by the Governor and State Legislature of the State of Deseret.

Ogden began to look for commerce. The establishment of the Farr's grist and saw mills in Ogden and the Daniel Burch's mills on the Weber River were major occurrences around 1850. In 1863, Jonathan Browning, James Horrocks, Arthur Stayner, William Pidcock and Samual Horrocks opened commercial businesses. David Peery later established the Ogden Branch of ZCMI in 1868. Fred J. Kiesel established the first industrial development in town. Later a woolen factory was constructed at the mouth of Ogden Canyon by Randall, Pugsley, Farr and Nell.

Shortly after these developments, the railroads came to Ogden. In 1869, the Union Pacific Railway building from the east and the Central Pacific Railway building from the west met at Promontory, Utah, for the famous Golden Spike Ceremony on May 10, 1869. In effect, this was the beginning of the transformation of Ogden from a frontier town to a rail terminus. In 1860 Ogden had a population of 1,463; by 1870, one year after the coming of the railroad, it increased to 3,127. During the following two decades, the population of Ogden doubled twice again to 6,069 in 1880 and to 12,809 in 1890.

The 1890's witnessed periods of boom and bust. The tremendous growth of the city, resulting largely from the arrival of the railroad, contributed to a tremendous surge of real estate development. Buildings sprang up all over and the city boundaries spread far beyond the old lines. The electrification of the streetcar lines in 1890 aided in this expansion. Unfortunately, the depression which gripped the entire nation in 1893 brought development to a standstill.

As the new century approached, Ogden began to make notable public improvements. Public utilities such as water, electricity, natural gas, and the telephones were established. In addition, the Ogden Rapid Transit Company was established in 1900 to serve Ogden and extended up Ogden Canyon to Huntsville. This line also served the growing livestock merchants as the Ogden Valley became a livestock center some fifteen years later.

The Prohibition period, which began in 1919 with the enactment of the 18th Amendment to the Constitution and lasted until 1933 when it was repealed by the 21st Amendment, caused few Ogden imbibers any hardship for lack of alcoholic beverages. The police department was suspected of bootlegging in 1920 and saloons remained open during Prohibition, except for the brief periods of raids by the police.

The Depression of 1929 struck Ogden as badly as the rest of the nation. Hundreds of workers were laid off. The New Deal public works projects initiated by President Roosevelt alleviated some of the unemployment problems. It was during this time that the Municipal Building, the Forest Service building, and the Ogden High School were built as part of the Public Works Administration programs.

When World War II began, Ogden was rescued from some of its economic hardships. The City became a center for defense installations. the Ogden Arsenal, Hill Air Force Base, Utah General Depot (Defense Depot of Ogden), and the U.S. Naval Supply Depot at Clearfield created many wartime jobs. The demand for jobs during the war led to a major demand for housing. As a consequence, Ogden and its neighboring cities began a surge in new housing starts.

In addition to the coming of the railroads and major defense sites, factors influencing the growth of Ogden were the headquarters of Conoco Oil, the flour mills, Del Monte plant and the cattle stockyards.

However, scandal hit Ogden during the war. Mayor Kent Bramwell assumed office in 1944 on the platform of cleaning up vice in the city. Word soon began to spread that Mayor Bramwell had been bought by Jack Meyers, recognized leader of the Ogden Racketeers and an entrepreneur on "Two-Bit Street." It seems the Mayor had reneged on 25th Street cleanup promises in return for money for his campaign. The major concern was with the police chief, who was determined to clean up 25th Street corruption. This scandal did contribute to cleaning up the Street, which was finally done in 1954. (See: http://www.ogden.navy.mil/history.html)

Picnic Dinner:

- Dutch oven cooking

Ogden Pioneer Days Rodeo

Timpanogos National Monument

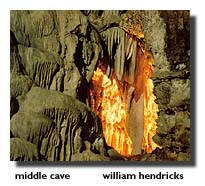

He followed mountain lion tracks and discovered an underground mystery, the legend goes. Martin Hansen, a Mormon settler from American Fork, happened upon a cave with colorful deposits, beautiful formations, and clear underground pools in 1887. The cave is named Hansen Cave, and it along with two other caves discovered later make up Timpanogos Cave National Monument.

The steep mountainside of American Fork canyon is the setting for these

limestone caves. Water, time, and rock formed the spectacular underground

scenery that exists inside. Natural forces created the caves as the Wasatch

Range grew 30 million years ago. Sedimentary rock was lifted and fractured along

fault lines. Naturally occurring carbonic acid then dissolved the rock, leaving

a hole that filled with water and later drained. The underground water dissolved

rock and left mineral deposits and forming crystals of different sizes and

shapes—a process that continues today.

The steep mountainside of American Fork canyon is the setting for these

limestone caves. Water, time, and rock formed the spectacular underground

scenery that exists inside. Natural forces created the caves as the Wasatch

Range grew 30 million years ago. Sedimentary rock was lifted and fractured along

fault lines. Naturally occurring carbonic acid then dissolved the rock, leaving

a hole that filled with water and later drained. The underground water dissolved

rock and left mineral deposits and forming crystals of different sizes and

shapes—a process that continues today.

(See: http://www.utah.com/nationalsites/timp_cave.htm)

Alpine Loop

This 20-mile drive winds through rugged alpine canyons of the Wasatch Range offering stupendous views of Mount Timpanogos and other glacier-carved peaks. The route follows Utah Hwy. 92 up American Fork Canyon and then continues through Uinta National Forest into Provo Canyon on U.S. 189

Sundance Resort

Centuries ago, the Ute Indians retreated to this canyon to escape the summer heat and hunt the abundant game. By the beginning of the Twentieth Century, the Stewarts, a family of Scottish immigrants, had settled the canyon. While the first generations were mostly surveyors and sheepherders, the next generation saw excitement and opportunity in the snow-laden slopes beneath Mount Timpanogos.

In the Fifties, the Stewarts opened Timphaven, a local ski resort which boasted a chair lift, a rope tow, and a burger joint named Ki-Te-Kai--Maori for "Come and get it!" (One of the Stewarts had served as a Mormon missionary to the islands.)

In 1969, Robert Redford bought Timphaven and much of the surrounding land from the Stewart family, and Sundance was born. Rejecting advice from New York investors to fill the canyon with an explosion of lucrative hotels and condominiums, Redford saw his newly acquired land as an ideal locale for environmental conservation and artistic experimentation.

official web site: http://www.sundanceresort.com/

Provo and Brigham Young University

Utah Valley was the traditional home of Ute Indians, who settled in

villages close to the lake both for protection from bellicose tribes to the

northeast and to be close to their primary source of food--fish from the lake.

The first white visitors to the Provo area were Fray Francisco Atanasio

Dominguez and Fray Silvestre Velez de Escalante, who visited Utah Valley in

1776. Only a retrenchment in Spanish New World colonization and missionary

efforts prevented establishment of settlements promised by these Franciscan

missionaries.

Fur trappers and traders frequented the area in the early decades of the

nineteenth century, and it is from one of these trappers, Etienne Provost, that

Provo takes its name.

Provo was settled by Mormons in 1849, and was the first Mormon colony in Utah

outside of Salt Lake Valley. Troubles with Indians gave rise to a popular saying

in early Utah: "Provo or hell!" When President James Buchanan sent United States

troops to Salt Lake City to put down the "Mormon insurrection" in 1858,

thousands of Mormons, including leader Brigham Young, moved to Provo. "The Move

South" came to a quick end as the Mormons were "pardoned" and new governor

Alfred Cumming made peace with the Saints.

Provo soon came to be known as the "Garden City" because of its extensive fruit

orchards, trees, and gardens.

In 1875 Brigham Young Academy was founded. From humble beginnings, this

institution has grown into Brigham Young University, the largest

church-affiliated university in the United States today. The city and the

university have enjoyed a symbiotic relationship and have grown together. Today,

the university has helped generate a fledgling high-technology industry in the

Provo area and sometimes attracts national attention through its academic and

sports programs.

Historically, Provo has served as the focal point of Utah Valley industry,

commerce, and government. Agriculture and the Provo Woolen Mills (which had its

origin in the Mormon cooperative movement of the late 1860s) served as Provo's

commercial staples in the late nineteenth century. Mining magnates such as Jesse

Knight, made rich by nearby precious-metal mines, made their homes in Provo and

helped create a thriving financial industry in the city. The coincidence of a

major water source and the intersection of two railroad lines led to the

completion in the Provo area of the Ironton steel mill in the early 1920s and

later the much larger Geneva steel plant. The railroads brought in needed raw

materials and transported finished steel products from Provo. Area residents

currently argue about whether the Geneva plant, which many assert is a major

cause of Provo's serious air pollution problems, should continue to be operated

or whether Provo should rely on new high technology as its industrial base. As

county seat of Utah County, Provo is the home of county offices and courts.

Provo has grown from a quiet, small Mormon city to a substantial modern

metropolitan area. Some of its traditional quaintness is gone, but its heart and

soul continue to thrive.

See:

http://www.media.utah.edu/UHE/p/PROVO.html; Kenneth L. Cannon II, A Very

Eligible Place: Provo and Orem, An Illustrated History (1987); J. Marinus

Jensen, History of Provo, Utah (1924); John Clifton Moffitt, The Story of Provo,

Utah (1975); John Clifton Moffitt and Marilyn McMeen, Provo: A Story of People

in Motion (1974); WPA Writers' Project, Provo: Pioneer Mormon City (1942).

Fort Douglas

The majority of the fort was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1970. The University of Utah Fort Douglas Heritage Commons is also an Official Project of Save America’s Treasures, a public-private partnership between the White House Millennium Council and the National Trust for Historic Preservation dedicated to the preservation of our nation’s irreplaceable historic and cultural treasures for future generations

Millcreek Canyon

For years, Millcreek Canyon has been a refuge for city dwellers. When the first white people came into the Salt Lake Valley in the 1840s they headed up the canyon to cut trees - hence the name 'mill.' Later, families came up to picnic and play and escape the heat. More recently, people have built summer homes and planned ski areas, though the summer homes are few in number and generally well hidden, and the ski area thing never worked out.

Millcreek is the most heavily wooded of all canyon abutting Salt Lake

City. The Salt Lake Valley is basically desert, and when settlers showed up in

the 1840s they found trees only right along watercourses. The canyons east of

town were logical places to turn. At the height of its use, there were 20

sawmills in Millcreek Canyon plus a few gold mines, and a well-used road chugged

up about seven miles of the canyon, and had sidetracks that wound up side

canyons.

(See:

http://www.utah.com/schmerker/2000/millcreek_canyon.htm)

Picnic Dinner

- Salad

- Rice and Beans

- Tortillas and fillings

- chips and salsa